“Praise dancing is a ministry,” says 17-year-old Ariana Starks at a recent Saturday morning practice at St. James, where she shimmied her shoulders to vibrant gospel music. “Most young people go to church and find it boring. This is a way to attract people into the house of God who wouldn’t normally want to come.”

In recent years, dance clothing stores and mail-order catalogs have begun selling praise-dance garments and props. Praise-dance Web sites are popping up, churches are hosting praise-dance concerts and conferences, and dance studios are offering classes.

Dance worship, or dance ministry, involves prayer movement, sacred dance and liturgical dance. It has a wide range of interpretations depending on the church and the denomination.

Give me reverence over relevance anytime.

…”The Catholic Church has been somewhat more resistant to liturgical dance,” says Susan Olsen, director of liturgy and music at Holy Family Parish in San Jose, which regularly incorporates dance into its Masses. “There are still some conservatives who wish we were still praying in Latin, and some who really want to keep the liturgy simpler.”

Resistant? How about outlawed.

NATIONAL CONFERENCE of CATHOLIC BISHOPS, all dancing, (ballet, children’s gesture as dancing, the clown liturgy) are not permitted to be “introduced into liturgical celebrations of any kind whatever.” [NATIONAL CONFERENCE OF CATHOLIC BISHOPS (BISHOPS’ COMMITTEE on the LITURGY) NEWSLETTER. APRIL/MAY 1982.]

I have joked before that the only dance allowed is on Sundays and Holy Days of Obligation is attendance. Outside of the Mass then you can dance as you like. King David did not dance in the Temple during the sacrificial offering. He danced in joy outside of a liturgical celebration.

Here is something from a site referenced in this article that specializes in Christian dance.

Give me pennants over penance! And for the brave of heart here is a Real Player movie of this.

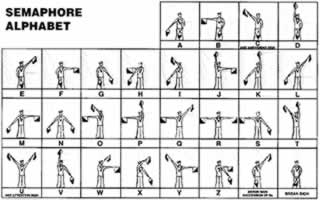

Now I was not a Signalman when I was in the Navy, but during Boot Camp we did have to learn something about the use of semaphore for signaling.

So using this I was able to translate the MPEG video shown here.

It as all about me, look at me here. Direct your attention on the dancers and their choreographed movements. My jumping around waving liturgical flags really makes you worship God more doesn’t it. Go ahead and admit it. You are now really deep in prayer, praying that I will stop and leave the sanctuary.

7 comments

This is one of the reasons why I felt uncomortable in the Charismatic Episcopal Church and had to leaVE.

::sigh::

A growing number of us young “kids” (at 22, I’m probably getting too old to use that word) prefer reverence over this silly “relevance” stuff as well. I saw this article right after I finished talking to a 20 year old seminarian and 19 year old friend about taking a roadtrip to Scranton for a Tridentine Mass. We’re all very excited about going to the old Latin Mass.

Thank for the precise translation. (I had deduced the message,but it is nice to have professional backup.)

I always made the analogy of liturgical dance to a car wreck. You never want to have either happen, but when it does you can’t seem to take your eyes off of it.

Thankfully our ‘pastoral associate’ who actually did her masters thesis on liturgical dance left. The new person (who’s new title is ‘director of faith formation’) hasn’t brought in liturgical dance to my knowledge.

I do know people who find dance to be prayful, but I always tell them that it’s wonderful that they find dance to be prayer, but it’s not appropriate prayer for mass. Just like Charismatic Catholics shouldn’t start praying in tounges in the middle of mass either – it’s a private thing.

Dance has become a monthly event at our church. I always want to duck out – if follows communion – but I know the kids and don’t want to hurt their feelings. Usually it’s just arm waving to Christian rap or gospel, although one girl is quite talented. I’m still not comfortable with it but I’m glad it’s just once a month. The sad thing is that not one of these kids could name 7 of the 10 commandments – I know these kids – but religious ed is pretty haphazard.

In the context of worshiping the Lord, I see dance as another expression. I have seen a congregation come together in spiritual warfare throught dance. I am delighted when the men and women of Israel DANCE and sing before the Lord following there victory after crossing the Sea.!!

The Lord has personally turned my mourning into dancing and I enjoy praising him when he leads me to.

HI. So it is known, I am not a Christian. I have been a devout Buddhist all my life. I have written a break down of liturgical dance world wide. Because liturgical dance exists in many different cultures, traditions and yes, religions, the essay I include here refers to all equally. Yes, there is a Christian movement to say that only such dance is liturgical. But my assertion is that as long as dance is sacred within the context of a, a liturgical component can be inferred to any doctrine and/or belief system.

Here is my article. It is in second draft, so I still have some editing to do, but I wanted to get some feed back to it. So, I hope at minimum, it is interesting, even if you disagree with it. -PHilip.

_______________________________________

What is Liturgical Dance?

Liturgical dance is often the most over looked dance in the world. What is neglected is that it is one of the two types of dance that grew out of movement as communication, before complete speech developed within current and ancient and pre- history. Because social and theatrical dance is most easily accessible to its audience and does not have the component of faith or usually a philosophical leap to understand or enjoy, it has historically overshadowed liturgical dance in recognition and cultural importance. What complicates this more is that many cultures� interpretation of their spirituality and religion forbids dance as either religious or secular expression, further reducing dance as a sacred expression.

A BRIEF HISTORY

Primitive movement pantomime was the first form of dance. It was more of a form of communication later accompanied by use of vocal emphasis to convey meaning. This occurred because no other form of communication had yet evolved. As human beings grew in the ability to communicate, vocal use of communication became dominant. This became �speech� and it has stood the test of time in becoming simpler and more effective method of communication. Because of this, in early human history, dance evolved into two distinct forms of expression: Social and Ritual Dance.

Social and Theatrical Dance

Social dance is a residual effect of the evolution of early forms of communication. Social dance is more localized an intimate and personal dance form that is meant to be done one on one, or in small groups. The basic idea of social dance is that it is to be danced by all participants, and observance of it is of secondary importance. Out of social dance grew theatrical dance, which is a more formalized presentational expression meant to be viewed by many people, and the dancers purpose is to �perform� for other people who do not participate as dancers.

Sacred Dance

But Ritual dance evolved because in the early years of primitive human and pre homo-sapien interaction, man had no way to gain understanding about his world. So, a variety of rituals evolved. These rituals have one main component which is the creation of an ecstatic state. The purpose of these ecstatic dances is to achieve one of three possible objectives:

1. to achieve an objective of spiritual union with the sacred objective,

2. spiritual communion with the sacred objective or

3. to achieve spiritual disengagement from the sacred and mundane.

IDENTIFYING SACRED DANCE

Cultural Associations of Referential Identification.

Because of the recent upsurge of dance in many North American Christian communities, the name �Liturgical Dance� has largely been associated with them. But, the term can have a wider definition.

Sacred, Spiritual and Ritual dance has thus been used to separate other religious dances from Christian. But, this assertion is only relative to such cognitive associations. Indeed the term �liturgical� may apply to many different spiritual beliefs and practices.

Synonymous Referential Identifications.

Many fundamentalist religious faithful as well as a few dance epistemologists might argue that there are differences between ritual dance, spiritual dance, sacred dance and liturgical dance. They would argue that if a dance that has nothing to do with the doctrine of a specific religion, it is only spiritual. Thus, dance that is not liturgical would does not directly use a liturgical libretto. These would include about half of the Christian liturgical dances that are becoming popular today. Yet, these are the dances that are still identified as �liturgical.�

Many of these cultures and religions may or may not include influences or direct reference to their religious doctrine in the dances themselves. But, because a liturgical association of can be inferred by the participants and viewers of a particular dance, all such dances must have both spirituality and liturgy as the purpose for performing them. Ergo, all spiritual, sacred, and religious dances can be considered �liturgical.�

Further, all liturgical dance can also be etymologically referred to as -ritual dance. This is because, the nature of the dances, whether choreographed or improvized, are a form a ritual unto themselves. So, all of these dances can be identified as �liturgical, spiritual, ritual and sacred.� In reference to dance, all of these terms are accurate and can be considered synonyms, with little or no segregate meaning between them. There is only one caveat to this: the linguistic and referential associations a certain group may have with a specific description.

THE FORMULA: What qualifies dance as liturgical and sacred:

– Most Importantly: Words and analysis such as these most certainly cheapen what liturgical dance is about. Thus, liturgical dance is -experiential- and tends to ground spiritual certainty (aka “faith”) in its practitioners, as a form of proof that their belief is correct. But we have to use words to gain understanding. To be specific, many who do not have, disagree with and/or resist religious belief and spiritual certainty may consider not being or should not be involved with liturgical dance other than as passive observers or passive participants as a form of gaining understanding into their world.

– All liturgical dances involve at least one of the following three components:

a) ritual or literal movement, choreography and/or improvisation upon a ritualized

theme.

b) artistry

c) myth and/or story.

But what sets liturgical dance apart from more mundane social, theatrical or secular dance is three specific things:

d) the dances can be defined as a form of -ritual- (This is so, whether or not they use

specified ritual within the choreography improvisation or not),

e) �ecstatic state- or ecstasy as either an objective or method of achieving the

objective which is inclusive of

f) spirituality and/or spiritual certainty/faith. Note, the use of myth and/or plot may

or may not be used in the dance, depending upon its type.

All liturgical dances must be ether:

1. specifically �transformative: the dancer dances to achieve another psychic relative form (animus) or absolute form (atman),

2. specifically �transcendent: the dancer dances to psychically transcend the human form or

3. a combination of transformative and transcendent: the dancer dances (path/method) to psychically transform his perception and idea of self and other (view/reasoning) causing him/her to psychically transcend �being� (fruition/result).

– All dances associated with it, must have an intuitive and emotionally driven foundation accompanied by logical rationale that supports it as representative of truth, in order to establish spiritual certainty about its objective. The religious and spiritual doctrines are the rational force and the practice of the dances and ritual are the emotional and intuitive force. These combined result in spiritual certainty or faith.

– All liturgical dance types and ecstatic dance work with and beyond the physical body into a state of joy. There are physical causations for this state such as adrenaline, endorphins etc. for this, but one might say that this is only symptomatic of the spiritual object of ecstasy. All liturgical dances use the relative concepts to get to know either

1. the ultimate world

2. ultimate beings, otherwise inaccessible in the relative world or

3. the ultimate side of relative being. (This is to say, the sacred side of oneself and/or another everyday being.)

One must first have spiritual certainty/faith before watching the dances to gain from their spiritual meaning, or one must gain such certainty during the dances in order to gain access this ultimate world.

– All liturgical dance has one or more of the following objectives to know or to commune with the ultimate world:

1. that which we don�t know or can now perceive in a relative way

2. that which we don�t know yet, or yet perceive in a relative way, and/or

3. that which we can never know, and will never perceive in a relative way.

THE FOUR TYPES

In short, there are four basic types of liturgical dance:

1) Dance as Communion, Communal Becoming, or Pure Ecstatic Dance. The Purpose of pure ecstatic dances of mostly theistic cultures is to place oneself as in unity with Other (God, Atman, etc.) In these dances such ecstasy is the objective. This form is specifically transcendent in nature.

These dances are usually found in European and Middle Eastern influenced monotheistic cultures. (Not all � the west has many influences elsewhere). Dance etymologists might call it ecstatic dance. This is the most basic type of liturgical dance. Its objective is to transcend the physical into a state of joy. There are physical causations for this state such as adrenaline, endorphins etc. for this, but one might say that this is only symptomatic of the spiritual object of ecstasy. Theistic cultures use such liturgical dance to ecstatically feel or “be” as one with God, or their belief thereof. These dances are most common in western European and Middle Eastern influenced cultures. Arguably, the most advanced, oldest and most traditional of the cultures that use this form of dance is the Sufi and Sufist Islamic cultures. There are also Christian ecstatic dances and dance groups, but these are relatively recent phenomenon. There are also many dances from most post Mesopotamian cultures from Israel to Morocco. These are very old dances that are pure ecstatic in orientation.

This form is probably the most recent on the evolutionary scale of liturgical dance. Its progenitors took a �leap of faith� to strip out doctrinal content to go straight to the essence to achieve ecstasy. It is the most simplistic in its method to achieve its goal. It is highly likely that this form of dance is also evolved out of pre-historical cultures that used ecstatic movement to achieve an end. So in this sense, it also may be the most ancient. This form of dance is lost in pre-history and we cannot know much about it, as it can only exist within us in an inherent sense.

2) Dance as Mythological Becoming, or Co-Associative Ecstatic Dance. The purpose of these dances is to place oneself as God or Other. These dances often use myth as a method conveyed by choreography and artistry to achieve a specified ecstatic state but here to transcend self to -become Other-. (God/Gods) This form is specifically transformative in nature.

In some cultures of the east, liturgical dance is very different from the west. The ecstatic component is only part of the method to achieve the purpose, as opposed to the objective itself. Dance is used as a description of myth, legend or religious philosophy. If the ecstatic state and joy overrides the form, then the meaning behind such a dance is lost.

The Indian forms of Baratanatyam, Odissi, and Katak dances all create an ecstatic state, but the performer must be grounded and aware of what he or she is doing technically, choreographically and artistically so that the ritual is realized to perfection. Many of the dances are performed the same as they were performed 3000 years ago, without change. There are many variations, but even many of these variations are thousands of years old. So, the training with lineage masters who have the honorific ‘master teacher’ or �Guru.� These dances are as exacting as the choreography. The young dancers are not encouraged to work into an overly ecstatic state. This is left for journeyman level dancers to develop. Why, because first technique and artistry is most important achieve. This is because ecstasy isn�t the goal, it�s only part of the method to get there. The ecstatic component is to be controlled by the performer. So mastery of form must be achieved so that an ecstatic state can be properly employed.

There is a second important version of the Associative Dance, and that is the past and current movement in liturgical dance in the Christian Church. Initially, the idea of �Passion Plays� were performed versions of stories from the bible. This has evolved into dance companies that perform choreographed pure ecstatic dances all the way to these Co-Associative plot based dances. But, it can be said that they draw too much from secular theatrical dance, to be a sacred form (it can lack the ecstatic component) or is a crossover form (See �Magical Blends�) drawing from both Pure Ecstatic Dance and Co-Associative dance. Nevertheless, there are several cultures and religions that use this form and crossovers between them.

The objective of this form of dance is to perform as god, or as �as the great whatever� thus not simply in unity with it. Any sense of unity created by ecstasy is only a means to an end. These types of dances are the second oldest form of liturgical dance in the world and survive in many cultures as a classical form in the India, Himalayas, near East, Southeast Asia the Polynesian and Micronesian cultures of the Pacific.

3) Dance as Literal Becoming, Entity Becoming or Associative Ecstatic Dance. Dance where the objective is utilitarian. These dances are used to become the spirit of a relative being. The primary objective is to gain something from another person, animal or object, whilst maintaining a sense of devotion to it. This is true whether the purpose is to

a) become the spirit of an object or animal, to

b) embody the animal or objects spirit in order to hunt it for food and other needs, or to

c) learn from it or to gain knowledge about �Other� from it. This form is specifically transformative in nature but may have a transcendent root and/or component to a specific dance.

In many Himalayan, Polar, African, Caribbean, Australian and some Native Central and South American cultures, the dancers� the purpose is more utilitarian. The oldest ritual choreography known in the world is the Yaqui Indian deer dance. It is said to have been carried with its lineage holders all the way back to the Baring Strait crossing of their ancestors. (There is argument by indigenous peoples regarding their own traditional mythological histories versus anthropological history; but this is another topic.) Indeed, there are several Mongol dances used for similar purposes that are virtually identical to Native American dances � and these dances are 5 minutes long!

The Yaqui Deer Dance is a hunter gatherer dance, where the performer embodies the essence of the deer�s spirit. Unlike the west�s use of anthropomorphic dances that humanize animals (a contemporary secular example is the Broadway production of �the Lion King�). Rather, the dancer here is using homeomorphism, where he is �animalizing� his humanity. Some cultures may use psychotropic botanicals to enhance the dance. But it is not used to just feel ecstatic; conversely, it is used to transform but not to transcend their humanity. We see this in the sacred shape shifters of many plains, rocky mountain, Inuit, Athabascan and other tribes with Asian earth based or Shamanistic regions as well as indigenous Australian and Siberian spiritualities.

In the dances of these cultures, again, ecstasy is a means to an end, but is not the objective of the dance itself. One is not in union with the spirit, one is the spirit!!

This is the most ancient form of dance and is the form from which all others arose. However, it is probable that this dance form evolved out of a type of Pure Ecstatic Dance, similar to the current Judeo/Christian/Islamic forms that consciously strip doctrinal content out of their dances to achieve ecstasy. Much of the information regarding this is lost to history.

4) Dance as Contemplative, Non-Becoming, Non-illusory or Non-Associative Dance. These dances use specific contemplative techniques, that are used to transcend form into ecstasy. And, then even to transcend ecstasy itself, in order to understand that all concepts of the relative world (creation/destruction, form, emotion, energy, ideas etc.) as well as concepts of Other (i.e. God, Atman, Great Spirit etc.) are as relative any other everyday experience. These are viewed as equal to, but no more real or not real than any form or idea. The component of contemplation and/or meditation is seen as the key to cognize the both the relative world (form) and ultimate world (emptiness), after all such concepts are transformed. The relative and the absolute are seen as the same. These cultures use forms such as meditation, contemplation combined with dance and visualizations to transcend form and thus transform ones mind as cognizant of these. The dances are seen as a path to first directly transform the dancers� view of self and other to secondly achieve a specifically transcendent objective to experience deeply the truth that all things are inherently empty in nature.

These Far-Eastern culture liturgical dances have evolved even further than their Shamanistic ancestry. The Buddhist and Taoist cultures use such sacred dances to transcend to be in union with the source of all form: which is formlessness. Thus, the form is used as a -contemplative- form. Here the ecstatic experience is seen as a somewhat irritating byway that one must transcend in order to understand that this to is just another manifestation of the relative world. The ultimate world can only be achieved by contemplation and meditation. Dance is one of many methods to do this.

This kind of liturgical dance is seen in the cultures of the Himalayas, China, Korea and Japan as well as early Zoroastrian Middle Eastern cultures. It is a strong component in all the marital arts. It was the need for self defense in the usually peaceful contemplative monasteries that the Asian martial arts were first conceived from migrating Indian (India) contemplative travelers who had learned ancient Indian martial techniques. These dances are non-theistic in nature, but uniquely use theistic symbolism as a direct means to dissociate from it. Though very close in the historical development to Dance as Mythological Becoming, Non-Asssociative Dance is the third oldest form of liturgical dance.

MAGICAL BLENDS

It must be established that there are gray areas between all these motivational types of dancing. Because all sacred dance is a form of ritual, because all the liturgically based dances eventual lead or go through an ecstatic state and because they are all grounded in spirituality, there is much cross over in dance type within single dances and/or from one dance to another within a certain group�s liturgical practice. These crossovers can most easily be found in contemporary dance liturgy.

4 Examples of crossovers of Dance Types within specific contemporary groups:

– The global organization the �Dances of Universal Peace� where groups meeting locally and in conventions of groups, fuses sacred dance, song and ritual and thus joins 3 types mentioned above from dance to dance, and sometimes within one dance itself in the form of communal dance. Most of these dances are circle dances and are most closely to ancient Mesopotamian dance. But influences can be drawn from Shamanic and agrarian culture�s dances as well.

– Recent Christian liturgical dance, especially in the US and Canada has many roots in theatrical dances such as Classical ballet and modern dance. It must be said though, that these dances are almost entirely based in the Pure Ecstatic Dance.

– And, there are the dances and rituals of the recent Wicca and Neo-Pagan sects. These Earth based Shamanic religious groups� utilize Associative Ecstatic Dances combined with the Pure Ecstatic Dances. Indeed, ancient hunter/ agrarian cultures may have used these combinations as well. The various Wiccan type groups may have used this kind of combination in their evolution of myth based upon their own ancestral myths legends and subsequent sacred histories. So, currently, a revival of this is richly growing in the west and it will be interesting to see how their dances evolve.

– Lastly, there is a contemporary movement to join both Social dance as well as Theatrical dance with liturgical ritual forms, or to infuse social or theatrical dance with a sacred spirituality. Depending on the spiritual and religious objective of each group, they may use any one of the four types of liturgical dance to achieve their objective.

(Note: Many secular social and theatrical dancers choose to make their dances spiritual in orientation. But, this is a silent personal choice within the context of performing secular dance. The dances they dance are considered to be strictly secular, even if given sacred associations by their performers. �The separation of church and dance,� one might say.)

The only conclusion that can be drawn from this is that dance, liturgical or otherwise, is �culturally based- and whether the group adheres to one form of liturgical dance or blends two or more of them, is grounded in a cultural imperative.

A BRIEF DEFINITION

Liturgical dance can be defined as dance that uses spiritually, ritual and ecstasy as a component to get in touch with the great unknown in the relative everyday world. The unknown may become known by infusing it with the sacred. The use of relative ritual creates a world where there is no need for hope and fear. This is because the question of what is the unknown is answered by the certainty created by the ecstatic state and/or by being able to transcend and/or transform the mundane world.

� 2004 Philip S. Rosemond

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Dance As Religious Studies by Doug Adams, Diane Apostolos-Cappadon Natl Book Network; May 1, 1990

Liturgical Dance A Practical Guide to Dancing in Worship by Deena Bess Sherman Express Press; May 2004

Worship as Meaning A Liturgical Theology for Late Modernity Cambridge Studies in Christian Doctrine by Graham Hughes, Daniel W. Hardy Editor

Cambridge University Press; September 11, 2003

Monk Dancers of Tibet by Mathew Ricard Shambhala; October 14, 2003

Dance Rituals of Experience by Jamake Highwater Oxford University Press; June 1, 1996

The Gods Come Dancing A Study of the Ritual Dance of Yamabushi Kagura by Irit Averbuch Cornell East Asia Cornell Univ East Asia Program; December 1, 1995

Ritual and Religion in the Making of Humanity (Cambridge Studies in Social and Cultural Anthropology) by Roy A. Rappaport, Meyer Fortes (Editor), Edmund Leach (Editor), Jack Goody (Editor), Stanley Tambiah (Editor) Cambridge University Press; March 25, 1999

Lord of the Dance: The Mani Rimdu Festival in Tibet and Nepal (Suny Series in Buddhist Studies by Richard J. Kohn State University of New York Press; June 1, 2001

Tibetan Sacred Dance A Journey into the Religious and Folk Traditions

by Ellen Pearlman Paperback

Inner Traditions International; November 30, 2002

Sweet Medicine The Continuing Role of the Sacred Arrows, the Sun Dance, and the Sacred Buffalo Hat in Northern Cheyenne History

by Peter J. Powell University of Oklahoma Press March 1, 1998

The Matachines Dance Ritual Symbolism and Interethnic Relations in the Upper Rio Grande Valley by Sylvia Rodriguez – Publications of the American Folklore Society.

University of New Mexico Press; September 1, 1969

Spiritual dance and walk An introduction from the work of Murshid Samuel L. Lewis Sufi Ahmed Murad Chisti

by Samuel L Lewis Sufi Islamia/Prophecy Publications 1983

Dance and Ritual Play in Greek Religion Ancient Society and History

by Steven H. Lonsdale Johns Hopkins Univ Pr; September 1, 1993

The Circle of the Sacred Dance Peter Deunov’s Paneurythmy

by David Lorimer Element Books; November 1, 1991

The Sacred Dance of India

by Mrinalini Sarabhai Paperback

Asia Book Corp of Amer; June 1, 1979

Dancing for themselves Folk, tribal, and ritual dance of India

by Mohan Khokar English Book Store; 1987

North American Indian Dances and Rituals

by Peter F. Copeland

Dover Publications; February 5, 1989

Dance as ritual drama and entertainment in the Gelede’ of the Ketu-Yoruba subgroup in West Africa by Benedict Ibitokune Awlowow University Press; 1993

Victory dances The story of Fred Berk, a modern day Jewish dancing master

by Judith Brin Ingber American distribution by Emmett Pub; 1985

Resources in Sacred Dance, 1991 Annotated Bibliography from Christian and Jewish Traditions Books, Booklets and Pamphlets, Articles and Serial Pub

by Keay Troxell Sacred Dance Guild; 1991 revision of 1986 ed edition May 1, 1991

Ritual in Early Modern Europe New Approaches to European History

by Edward Muir, William Beik Editor, T. C. W. Blanning Editor Cambridge University Press; August 28, 1997

Sacred Pleasure Sex, Myth, and the Politics of the Body–New Paths to Power and Love

by Riane Eisler HarperSanFrancisco; 1st edition June 14, 1996

Women As Ritual Experts The Religious Lives of Elderly Jewish Women in Jerusalem American Folklore Society, New Series

by Susan Starr Sered Oxford University Press; New Ed edition October 1, 1996

Ancient Ways Reclaiming Pagan Traditions Llewellyn’s Practical Magick Series

by Pauline Campanelli, Dan Campanelli Llewellyn Publications; 1st ed edition September 1, 1991

Ritual Theory, Ritual Practice

by Catherine Bell Oxford University Press; New Ed edition April 1, 1995

Ritual and Religion in the Making of Humanity Cambridge Studies in Social and Cultural Anthropology by Roy A. Rappaport, Meyer Fortes Editor, Edmund Leach Editor, Jack Goody Editor, Stanley Tambiah Editor Cambridge University Press; March 25, 1999

Readings in Ritual Studies by Ronald L. Grimes Pearson Allyn & Bacon; 1 edition November 30, 1995

Deer Dance: Yaqui Legends of Life

by Stan Padilla Book Publishing Company (TN); August 1, 1998

Escapism by Yi-Fu Tuan Johns Hopkins University Press; July 1, 2000

The King’s Body: Sacred Rituals of Power in Medieval and Early Modern Europe

by Sergio Bertelli, R. Burr Litchfield Pennsylvania State University Press; November 1, 2001

East Meets West in Dance: Voices in the Cross-Cultural Dialogue (Choreography and Dance Studies Series) by Ruth Solomon, John Solomon Routledge; May 1, 1995

Taoist Ritual and Popular Cults of Southeast China

by Kenneth Dean Princeton University Press; September 18, 1995

Flip, out.